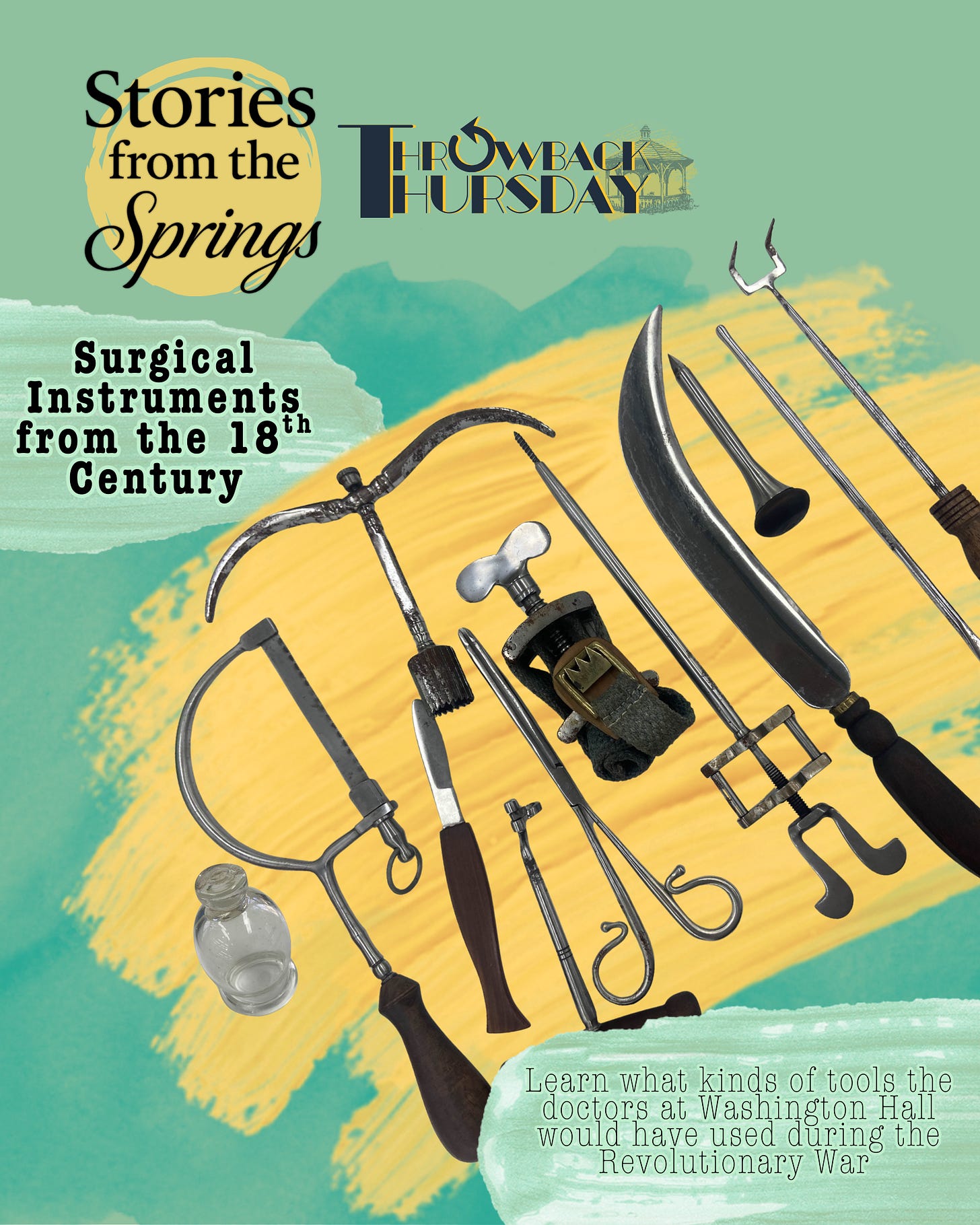

Throwback Thursday: Medical Tools of the Revolution

As We Explore the Medicine of the 18th Century, The Uses of these Tools Intrigued Us

Tools of The Trade

As the Moore Archives prepares for our upcoming exhibitions focused on the Revolutionary War and the medical tools that saved soldiers’ lives at Washington Hall, we would like to take a moment to identify and explain some of the medical instruments on display. For several years, a display case in the Brick Room of the Lincoln Building on our campus has showcased a collection of replica 18th-century tools, which recreate the medical kit of Dr. Bodo Otto.

These rather intense-looking instruments can evoke images of surgical horror stories. From our current perspective in medical history, it is easy to see these types of tools as blunt and brutish. However, that is not the case. Although they may appear to be instruments of torture or something that a serial killer might use, during the 18th century, they were considered highly advanced and state-of-the-art.

The thought of a bone saw being used to provide care to a dying patriot might conjure up dreadful tales of what hospitals used to be like, but as we examine the past, it is important to remember that the advancement of medicine has been built on the contributions of many great minds. As we progress, it is vital to take a moment to reflect on how we arrived at this point in medical history. And sometimes, that means identifying what tools medical practitioners used to make the Age of Agony a little less torturous.

Though it must be pointed out-- without modern anesthesia and pain relief, these surgeries and treatments would probably still have hurt a lot.

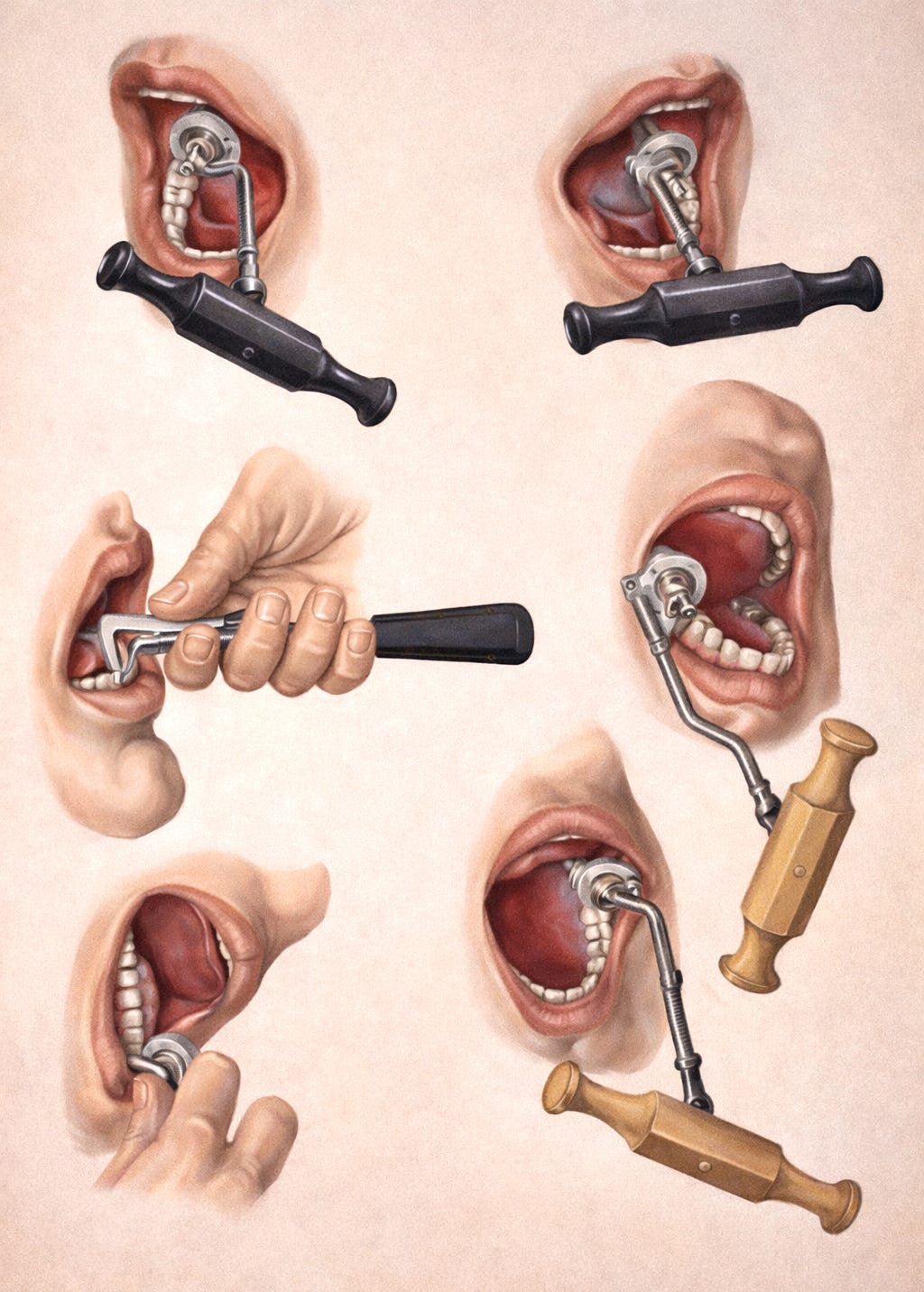

Tooth key

The tooth key, also known as a dental key, was an instrument used in dentistry for extracting diseased teeth.

Before the invention of antibiotics, dental extractions were often the preferred method for treating dental infections, and extraction instruments have been in use for several centuries.

The tooth key, which is also referred to as the Clef de Garengeot, Fothergill Key, English Key, or Dimppel Extractor, was first mentioned in Alexander Monro’s “Medical Essays and Observations” in 1742, although it likely had been in use since around 1730.

The dental key remained popular well into the 20th century, until it was eventually replaced by more modern dental forceps.

Cupping Glass

The history of cupping as a therapeutic practice is extensive but largely undocumented.

In ancient Greece, Hippocrates (460-370 BCE) used cupping to address internal diseases and structural issues, while Roman surgeons applied it for bloodletting as well. The method was highly endorsed by the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, leading Muslim scientists to further develop and refine the practice. As a result, cupping spread across various cultures in Asia and Europe.

In China, the earliest recorded use of cupping comes from the Taoist alchemist and herbalist Ge Hong (281–341 CE). Cupping was also referenced in Maimonides’ health writings and was practiced within the Eastern European Jewish community. In the early twentieth century, William Osler recommended cupping for pneumonia and acute myelitis.

During the 1770s in colonial America, doctors used cupping to “draw out” illnesses, especially those believed to stem from excess fluids, such as inflammation, fevers, chest congestion, headaches, or joint pain. The underlying concept was that by pulling blood toward the skin, pressure could be relieved from deeper inside the body.

The cupping process was fairly straightforward, though not particularly relaxing.

A practitioner would place a small glass cup on the skin and create suction, often by briefly heating the air inside the cup with a flame and then applying it to the skin, allowing the cooling air to pull the skin upward. This technique left a raised, dark mark.

Cupping could be done “dry,” involving just suction, or “wet,” where the skin was lightly cut to allow blood to be drawn into the cup. At the time, people viewed this as a practical, hands-on method to alleviate pain and “rebalance” the body, even if today it prompts gratitude for modern clinics and sterile equipment.

Mug

In the 1770s, redware mugs (everyday pottery made from locally sourced reddish clay) were not considered “medical equipment,” but they played an important role in caregiving.

These mugs were commonly used to serve sick individuals warm drinks and soft foods like broth, tea, or thin gruel. This practice was significant because colonial medicine heavily relied on basic supportive care, which focused on keeping patients hydrated, comfortable, and strong enough to recover.

Warm liquids were easier to swallow, gentler on weak stomachs, and comforting during fevers or chest ailments. Additionally, redware mugs could retain heat better than thin metal cups. The process was straightforward: a caregiver would heat broth or an herbal drink at the hearth, pour it into a redware mug, and then bring it to the bedside, offering small sips or spoonfuls throughout the day.

In a time without modern hospitals, IV fluids, or insulated containers, these ordinary mugs became an essential part of the daily routine for ensuring that patients remained nourished and stable.

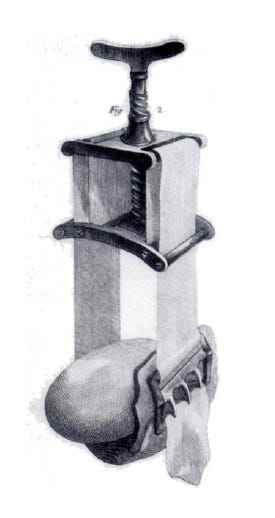

Trephine

In the 1770s, this colonial surgical tool was known as a trephine, which was used to cut a neat circular hole in bone, most famously in the skull. The trephine featured a short metal cylinder with a sharp edge, operated by a turning handle that allowed it to “core” out a round piece of bone.

The procedure known as trepanning (or trepanation) involved the surgeon using this tool, or other cutting methods, to open the skull. This was typically performed after serious head injuries, such as fractures, or when doctors suspected that pressure or trapped blood inside the skull was causing dangerous symptoms.

The process was quite blunt and physical: first, the scalp would be cut and pulled back, then the trephine was carefully rotated to remove a small disc of skull, exposing the underlying tissue.

During a time without modern imaging technology, antibiotics, or safe anesthesia, this operation was considered risky. Nevertheless, the surgeons who performed it believed it was one of the few methods available to relieve pressure and prevent death following severe trauma to the skull (and other large bones).

Interestingly, trepanation is one of the earliest surgeries for which we have archaeological evidence. By the 1770s, while the tools used in the process had advanced, the procedure itself remained largely unchanged.

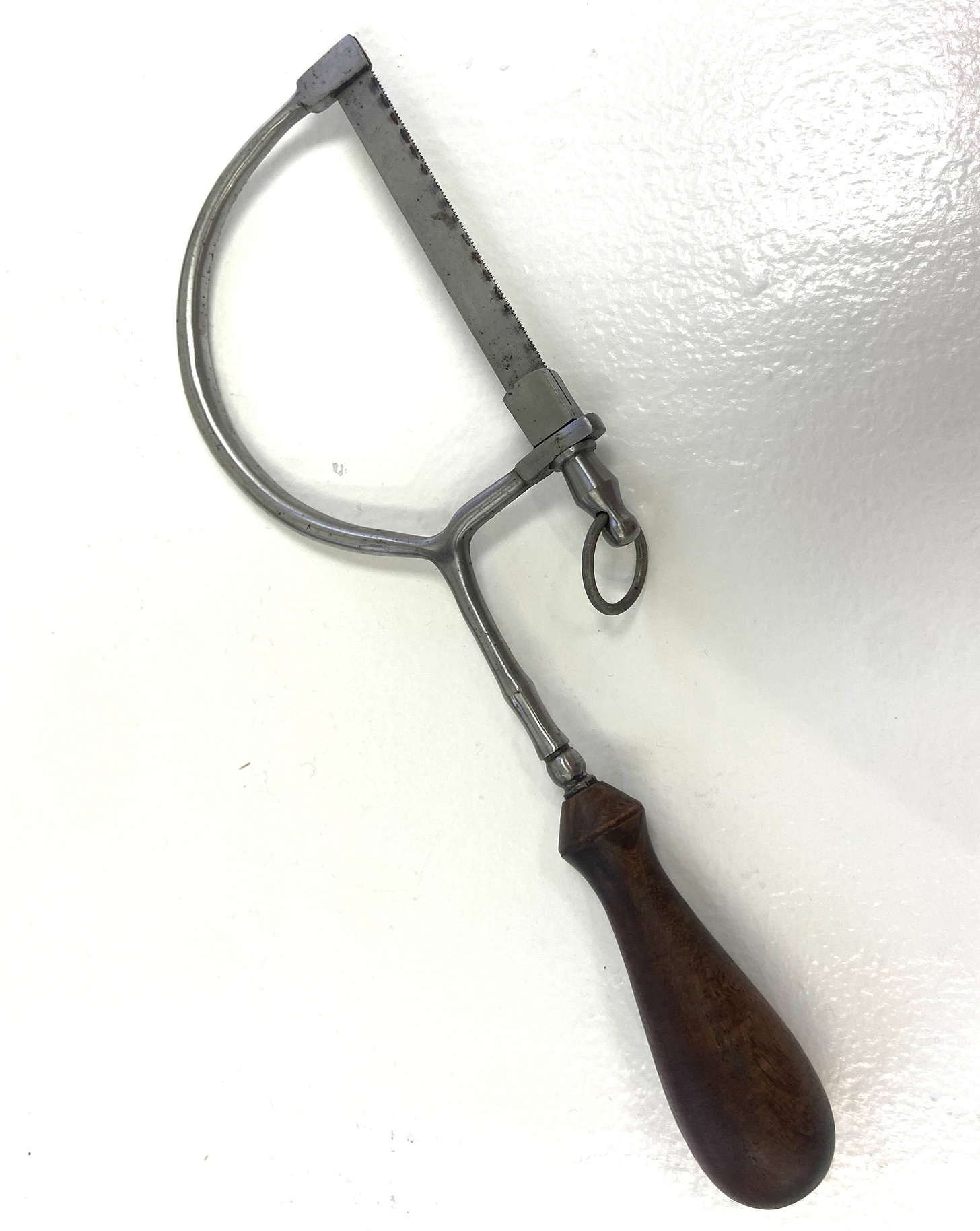

Metacarpal Saw

A metacarpal saw is a specialized surgical instrument, featuring a narrow, serrated blade designed for the precise cutting of small bones, particularly the metacarpals (small finger bones, the “middle knuckles”) in the hand. This instrument is commonly used during procedures such as fracture repair or amputation.

Made from durable steel, the metacarpal saw can be sterilized and reused. These saws allowed surgeons to make clean cuts on delicate hand bones, minimizing trauma to the surrounding tissue. The saw was designed to fit within a surgeon’s box of instruments. Its fine teeth are suitable for cutting bone without needing the larger “capital” saw used for arms or legs.

The process typically involves several steps. First, the surgeon makes an incision through the skin and muscle to reach the bone, exposing the injured metacarpal bones. The metacarpal saw is then used to carefully cut through these bones, enabling the surgeon to remove broken segments or perform a partial amputation. The primary goals during this procedure are speed and precision, as quicker cutting reduces the time a patient experiences pain and bleeding. At that time, there was no modern anesthesia, and infection control methods were minimal, making efficient operations crucial.

Although modern techniques and tools have greatly improved, metacarpal saws were essential for treating severe hand injuries in the 18th century.

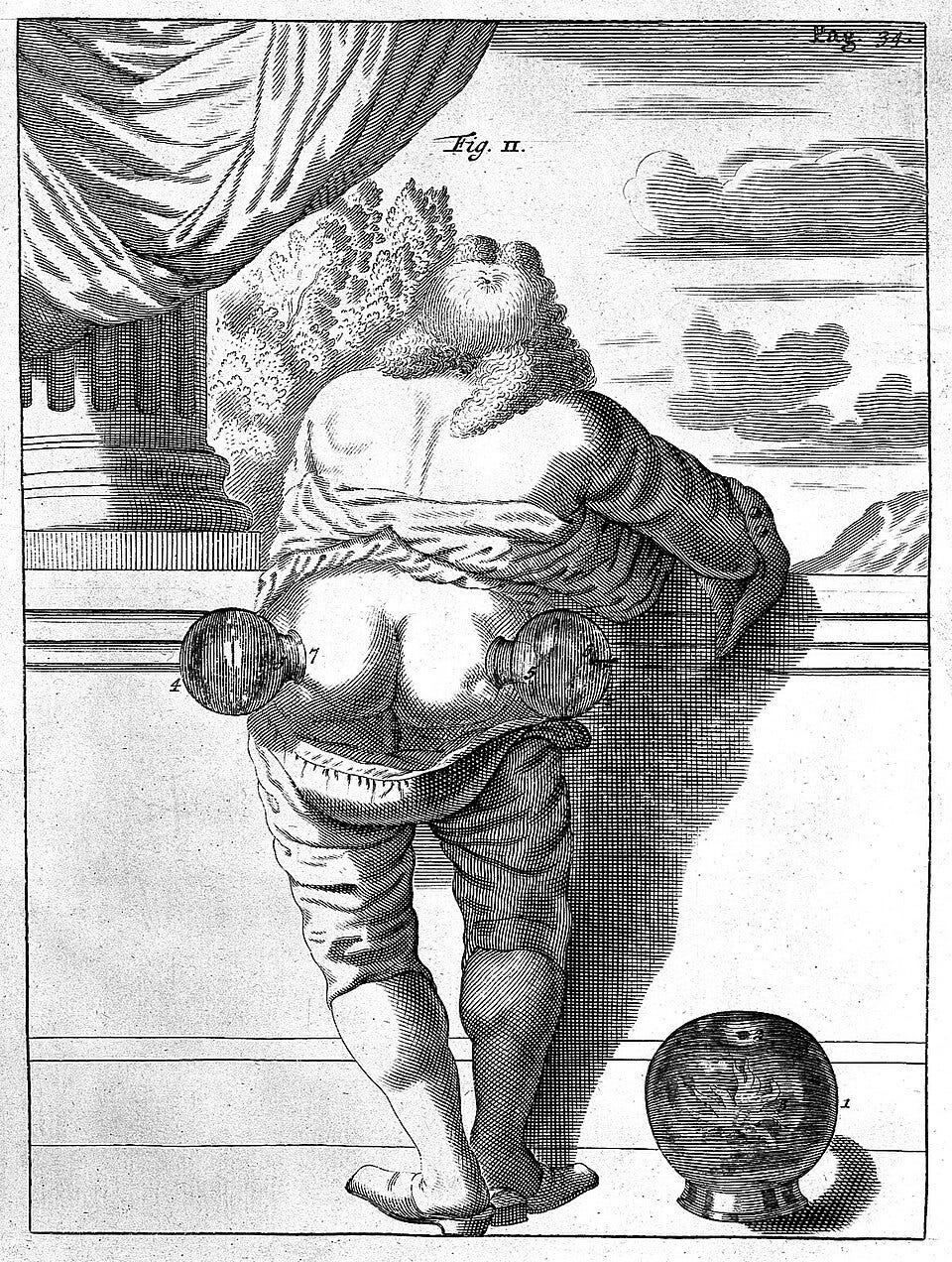

Tourniquet

In the 1770s, colonial medicine employed a tourniquet as a simple yet crucial tool used by surgeons to control bleeding during severe injuries or amputations.

The basic concept involved wrapping a band or strap around a limb (either an arm or a leg) and tightening it until blood flow was reduced or stopped. This provided the surgeon with a clearer field of vision and helped prevent the patient from bleeding to death during surgery or after a traumatic injury.

The term “tourniquet” is derived from the French word “tourner,” which means “to turn.” This relates to the early devices that often used a stick or rod to twist and tighten the band around the limb. Such devices were included in surgical kits from the late 17th and 18th centuries and were particularly associated with battlefield and amputation medicine, as wounds from muskets, swords, and accidents frequently resulted in dangerous bleeding.

The process for applying a tourniquet was as follows: a surgeon or assistant would take a strip of linen, leather, or cloth and wrap it several times around the upper part of the injured limb. Next, they would insert a stick or rod into the knot and twist it to tighten the band, applying firm pressure on the arteries to slow blood flow down the arm or leg. Once the bleeding was reduced, the surgeon could then work on the wound or perform an amputation with improved control over blood loss.

Given that anesthesia and sterile techniques had not yet been developed, speed and control were essential. The tourniquet offered physicians a rudimentary means to manage one of surgery’s greatest dangers: uncontrollable bleeding.

Double Retractor

In the 1770s and during the era of colonial medicine, this tool featured two ends or blades specifically designed to hold back skin, muscle, or other tissues during surgery, allowing the surgeon to see and operate more easily. Retractors, in general, are instruments crafted to separate the edges of a wound or incision, keeping tissues out of the way and providing the surgeon clear access to the area being treated.

While most of the named retractors we recognize today, such as the Senn or Army-Navy retractors, were developed later, the fundamental concept of retractors was already well understood by surgeons before the 19th century.

They needed tools that could replicate the action of human hands pulling tissue aside once an incision was made, which was particularly important for deeper wounds where fingers alone were insufficient. Early versions of retractors were often simple, consisting of hooked pieces of metal or shaped blades attached to handles. A “double” retractor offered useful symmetry, with blades on both ends, enabling a surgeon to flip it around and retract tissue in different directions without needing multiple tools.

The usage of a double retractor was practical: after making an incision through the skin and muscle to access the surgical site, the surgeon or an assistant would insert one end of the retractor into the incision and gently pull back the edges of the tissue. This held the wound open and out of the way, allowing the surgeon to visualize structures like bone or deeper organs and operate with greater precision. Maintaining a clear view was crucial in an era without anesthesia or modern lighting, as reducing the duration and complexity of the procedure could help lessen pain and decrease complications.

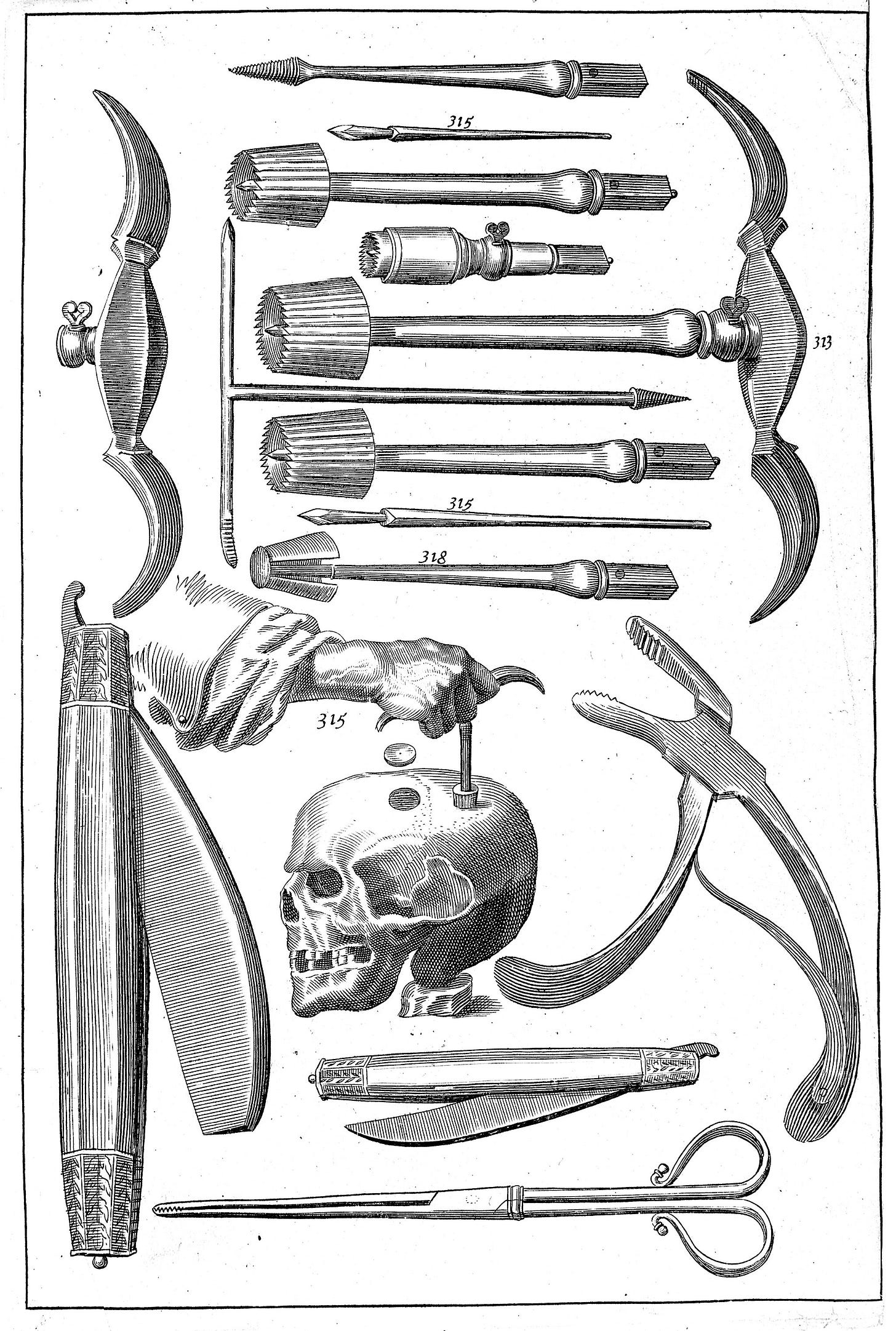

Bullet Probe

During this era of medicine, a bullet probe was a long, slender, needle-like surgical instrument used to locate a musket ball or other debris lodged deep inside a wound. Gunshot injuries were quite common in wartime, and surgeons needed a method to follow the wound’s path without immediately widening the incision.

The probe, typically made of metal and featuring a smooth or rounded tip, could be gently inserted into the wound channel, allowing the surgeon to feel for the hard bullet, broken bone, or fabric pushed into the wound by the shot.

Once the projectile was located, the surgeon might attempt to remove it using forceps or decide it was safer to leave it in place if further digging could cause more damage. This process was painful and risky, given the limited availability of anesthesia and the high risk of infection during that time. Nevertheless, probing helped surgeons understand what was happening beneath the skin and choose the next appropriate step in the treatment.

Ball forceps

In the 1770s, colonial medicine utilized ball forceps (also often referred to as bullet forceps) as a surgical tool for retrieving musket balls from wounds, particularly when the balls became lodged in soft tissue. These instruments resembled long metal tongs with narrow jaws designed to reach into a wound and securely grip the smooth, rounded lead balls without slipping.

This capability was crucial because musket balls could carry dirt, cloth, and bone fragments into the body, and failing to remove the ball could lead to increased pain, swelling, and a heightened risk of infection.

The procedure was somewhat rough but effective: after examining the wound, a surgeon would first use a probe to locate the musket ball.

Next, they would insert the ball forceps into the wound track, grip the ball, and carefully pull it out with a steady motion. However, if the ball was too deeply embedded or if removal posed a greater risk of damage, surgeons might choose to leave it in place.

When possible, though, ball forceps were one of the primary tools used for extracting the musket ball.

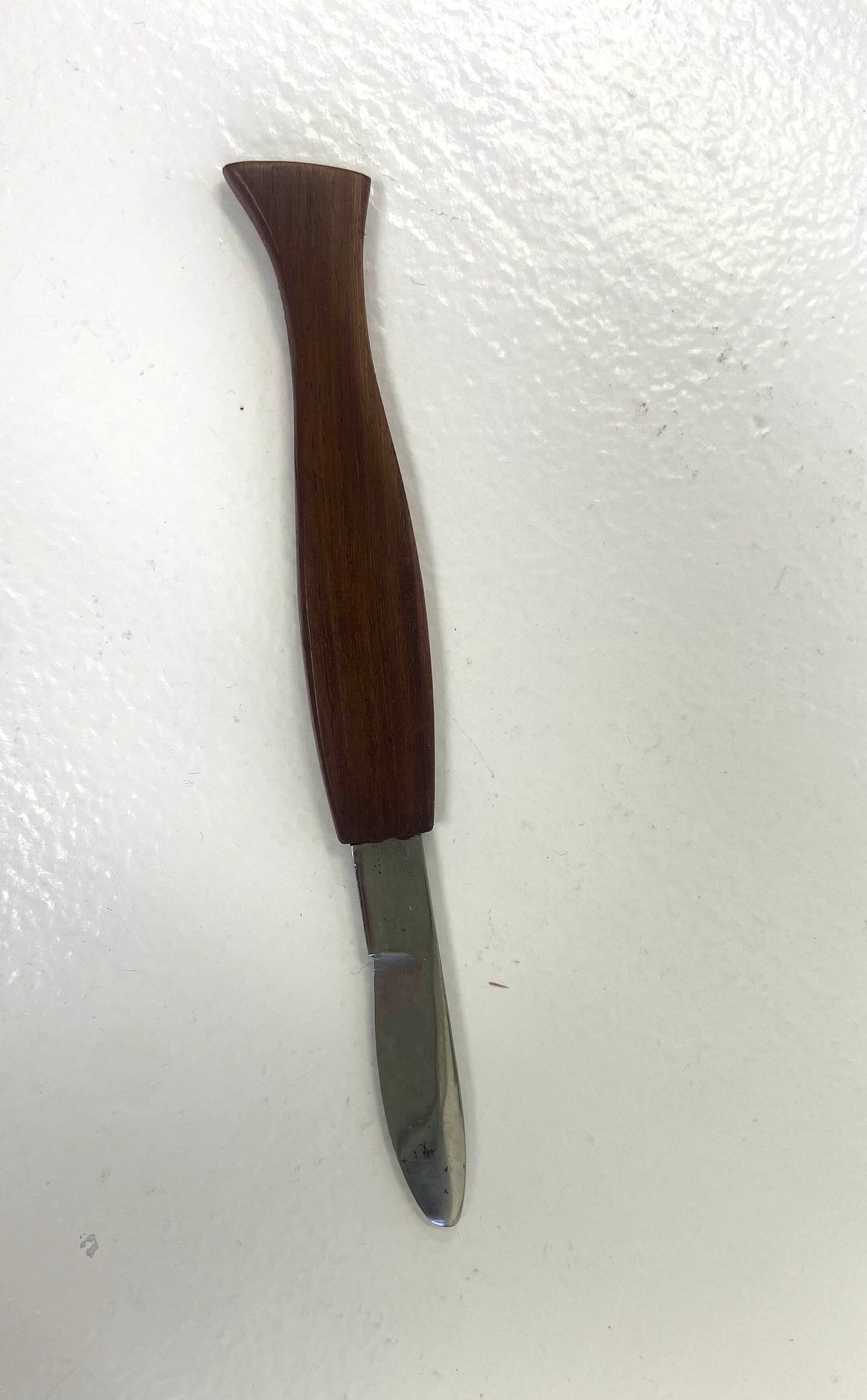

Scalpel

During the later part of the 18th century, a scalpel was a small, very sharp knife used by surgeons to make incisions: precise cuts in the skin and tissues. Oftentimes, the scalpel was considered the most important tool in a medical man’s trunk. A surgeon without a scalpel was like an artist without her paints.

It was the primary cutting tool for almost any surgical procedure, including opening wounds, enlarging them gently to allow for better visibility, removing diseased tissue, and even extracting embedded objects.

The term “scalpel” comes from the Latin word “scalpere,” which means “to cut.” The blades were typically made of metal designed for repeated use.

Although medical knowledge of infection and pain control was limited during colonial times, the scalpel remained essential because it offered surgeons greater control over the location of cuts and helped to expedite procedures that would have been much more traumatic with less precise tools.

Trocar

In the 1700s, a trocar was a sharp, pointed instrument housed within a hollow tube called a cannula.

Doctors used this tool to intentionally create an access point into the body. Although it was developed before the 19th century, early trocars were primarily designed to drain excess fluid or gas, particularly when a patient had a dangerous buildup in their chest or abdomen due to injury or illness.

The surgeon would press the pointed tip through the skin and underlying tissue, allowing trapped fluid to escape and relieving pressure.

Over time, similar designs evolved to serve as entry points for introducing other surgical instruments, but the fundamental purpose remained the same: to create a controlled opening that safely provided access to the body’s interior during colonial surgical procedures.

Fleam

A fleam (also known as a flem or flew) was an archaic instrument used for bloodletting during the 17th and 18th centuries. At that time, bloodletting was considered a vital aspect of medicine, believed to be essential for balancing the “sanguinity” of a person. The four humors theory was the prevailing understanding of the human body, and bloodletting was an integral part of many treatment plans.

The fleam was specifically designed to puncture a vein and facilitate blood removal. It featured a flat handle and a sharp, angled blade, or sometimes multiple blades. When pressed or struck with a small stick, the fleam would quickly open the vein while minimizing damage to the surrounding tissue. Bloodletting was commonly used to treat various conditions, as doctors believed that removing “bad blood” would restore balance to the body’s humors.

Though the fleam eventually became more associated with veterinary use, it was still commonly found in medical kits meant for treating human patients, often alongside simpler ‘lancets’- small, sharp medical devices with a needle or blade are used to puncture the skin and obtain a tiny blood sample for testing.

Capital knife

In the 1770s, the capital knife was a large and sturdy surgical knife specifically designed for amputations.

The term “capital” referred to major surgical operations, and this knife was intended for one primary purpose: to cut quickly and cleanly through the body’s outer layers to reach the bone. For smaller surgeries, smaller tools- such as the metatarsal saw we mentioned earlier- were employed.

In practice, the surgeon would first try to control bleeding as effectively as possible, often using a tourniquet. Then, they would use the capital knife to slice through the skin and the underlying tissue (both cutaneous and subcutaneous), opening the limb to access deeper structures. Speed was crucial in these procedures due to the lack of effective anesthesia and the constant danger of heavy bleeding, making a sharp and reliable knife essential for surgeons to work more quickly and with greater control. Once the soft tissues were separated, additional tools, such as saws, were employed to cut through the bone and complete the amputation.

Mortar and pestle

During this era, the mortar and pestle were among the most crucial tools in colonial medicine, as they were essential for preparing many remedies. The mortar is a heavy bowl, while the pestle is a grinding tool used to crush and mix various ingredients, such as herbs, roots, seeds, resins, and minerals, into powders or pastes.

This process was vital because colonial medicine relied heavily on plant-based treatments. Caregivers or apothecaries would grind dried herbs and then blend them into drinks, syrups, poultices, or salves.

The preparation was hands-on: the ingredients, whether dried or fresh, were ground to a consistent texture and then mixed with substances like water, alcohol, vinegar, honey, or fat. This allowed the resulting medicine to be swallowed, applied to the skin, or packed into cloth to treat wounds.

In an era without factory-made pills, the mortar and pestle transformed raw plants into usable medicine.

To Us, Today

As we reflect on the medical practices during the Revolutionary War and examine the tools that saved lives at Washington Hall, it becomes clear that understanding these instruments goes beyond simply recognizing unusual objects displayed on pedestals for our viewing pleasure.

Learning what each tool was used for (and why) helps us see the 18th century on its own terms, not as a period of careless cruelty, but as an era of problem-solving, improvisation, and hard-earned skill in the face of injury, infection, and uncertainty.

For the people who relied on them, these instruments were not symbols of barbarism; they represented the best available answers to urgent, life-or-death questions, used by practitioners doing everything they could with the knowledge and resources at their disposal.

Today, when modern medicine may seem almost effortless- thanks to sterile rooms, anesthesia, antibiotics, and precise digital imaging- it is easy to overlook the long history of trial, experience, and courage that led to these advances.

These tools serve as a reminder that medical progress did not happen overnight; it was built through generations of observation and necessity, often in conditions we would now find unimaginable. Remembering this era honors both the medical professionals who worked under extreme limitations and the patients; soldiers and civilians alike; who endured painful and risky treatments that were sometimes their only chance at survival.

While these instruments may still make us wince, that reaction is part of the message. The “Age of Agony” deserves to be remembered not for shock value, but because it illustrates how far we’ve come and the immense human determination that made it possible to get here.

🔪🪡✂️

See more online at: Historic Yellow Springs

🔪🪡✂️